Deconstructing Authority: William Greaves’s Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take One

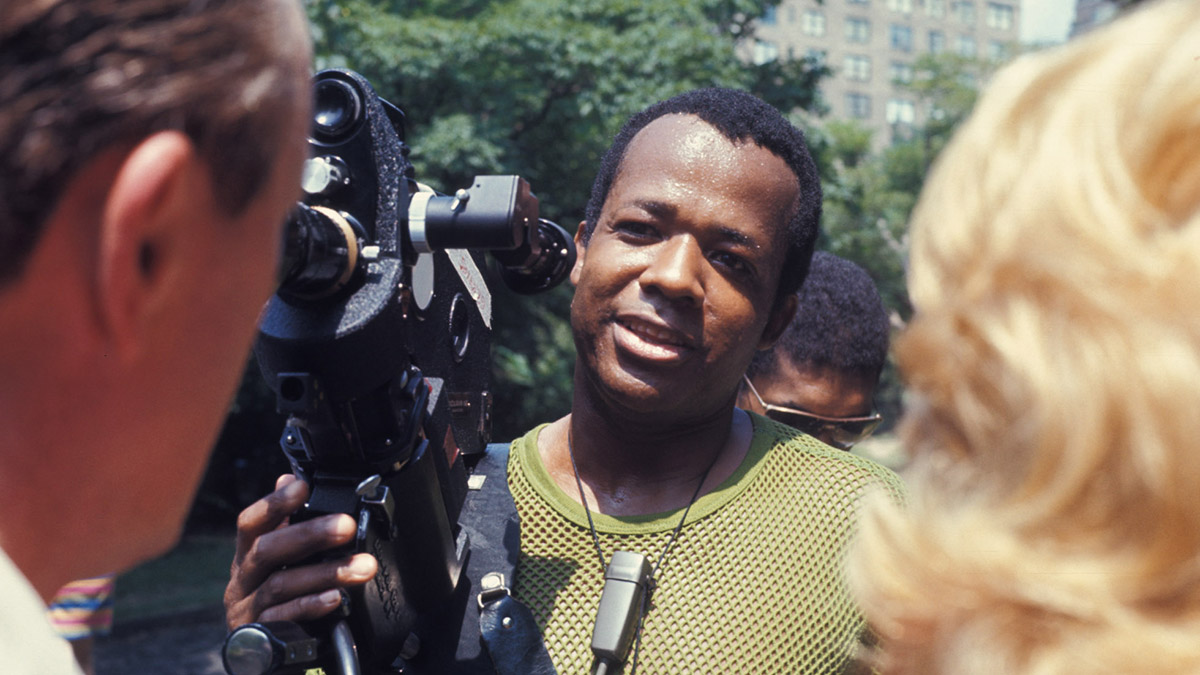

Critics Campus 2023 participant Christy Tan takes a look at the political and aesthetic questions posed by William Greaves’s radical 1968 docufiction experiment.

In a secluded corner of Central Park, a man and a woman stage the breakdown of their marriage. They are followed by a succession of different actors re-enacting the same situation; all are unable to escape the entrapment of heteronormative cliché, a microcosm of a society in decline. As the screen splits and alternates between the original husband and wife, the intimate scene is abruptly punctured by a film crew: suddenly, the couple is in full public view, with indifferent onlookers peering through bespectacled eyes. The microphone feedback heightens, opening up to the surrounding area and its mobile inhabitants. A Miles Davis jazz score breezes through the trees, echoing the camera’s perpetual flux.

In Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take One (1968), William Greaves’s genre-evading documentary, there is no central protagonist or plot tying these disparate threads together; instead, our focus is constantly shifting and rematerialising. Shot using three cameras – one tasked with filming the actors, the second filming the first and the third documenting the entire process, including its environment and spectators – Symbiopsychotaxiplasm is a documentary about the process of its own making, appropriating its own formal failure to complicate the medium further.

This disorientation is politically subversive, too; every camera perspective, sometimes shown side by side, gives each representation equal framing and enables different connections and contradictions to flourish. As different details leak out of each frame, what unfolds is not the hierarchy of one point of view, but instead multiplicity and collaboration, mobilised through the film’s disruptive ways of seeing and listening.

In showing multiple layers of reality being captured, Symbiopsychotaxiplasm is cinema vérité that is aware of its own artifice. The handheld camera grooves to the saxophone that plays over footage of bystanders, emphasising the unstable and irreducible whole that can never be directly accessed. Not only does the documentary refuse to conceal the slippery slope between truth and fiction, but it also exposes the cracks held together by their mutual dependence. The different screens are ordered with no clear logic, demonstrating the generative disruption of incoherence.

These scenes resist being totalised into a monolith, pre-empting and inverting any potential narrative hegemony that might be enacted. The film’s kinetic energy catapults the viewer into the feeling that, wherever you look, something is happening – or about to happen – elsewhere. Every presence that is depicted is shadowed by a conterminous absence, impossible to convey through the limited confines of a conventional, singular perspective. The changing cameras demand a constant repositioning of each subject and spectator, decentring a reified order from foreclosing interpretation.

Seeking to undermine calcified and habitual ways of seeing, the film addresses the question not of what to show, but of how to shape an audience’s capacity to engage with the world in all its fracturing and proliferating possibility. The flittering camera movements destabilise the grounds of our attention, making us acutely aware of how we are always already present in whatever we are observing, collapsing the precarious distance between subject and object. This kind of relationality is what the title of Symbiopsychotaxiplasm – which literally refers to the reciprocal effective relationship between experience and the human psyche – implies: the multi-directional gaze that is produced when the presence of a camera elicits a kind of contagious self-reflexivity.

Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take One

Adding another layer of complexity, Greaves plays a blundering and oblivious version of himself – unbeknown to the crew and actors, who all begrudgingly submit to his vague and unhelpful direction. Even when there are technical issues or he is behaving in a misogynistic manner, they mostly respond with compliance, adhering to their prescribed roles in the unspoken pecking order, reluctant to violate any professional boundaries.

The crew’s resistance only comes to fruition in the director’s absence, secretly recording themselves in a separate room. They contest and debate his incompetence and their growing discontent with his lack of direction; though, as one crew member points out, it’s precisely Greaves’s lack of direction that has compelled them to collectively intervene and “function like a chorus”.

This unscripted revolt is a manifestation of the film’s anti-authoritarian praxis. Greaves later admitted that he deliberately acted in such a way so as to provoke a rebellion and metacritique of the film, seeking to test the point at which the actors and crew would no longer endure his ineptitude and intentionally counter the socially constructed authority embedded in his position. In doing so, he explored the spontaneity and improvisation that might come out of collective intervention and the decentralising of power, in contrast with deferring to any one person’s vision.

Greaves’s background was in theatre, but the lack of meaningful roles for African-American actors at the time – as well as the political upheavals of the 1960s and their ensuing radical movements – diverted him towards documentary as a tool for consciousness-raising. He was one of very few Black filmmakers of the era recognised for his experimental style, an approach often only associated with white artists.

Artists of colour were, and still are, repeatedly subjected to the false dichotomy between politics and aesthetics: if a film is received by audiences as political, its aesthetics are often ignored or seen as peripheral to its central thesis; inversely, when a film is recognised and lauded for its aesthetics, the underlying politics that shape and structure it are often disregarded. This approach overlooks the ways in which aesthetic choices – conscious or otherwise – and politics are inextricably bound.

Symbiopsychotaxiplasm is a case in point: although not overtly about race in its content, its subversive politics manifests through its experimental form. Greaves made this film not in spite of being a racialised Other, but because of it: his marginalised positionality, translated into an outré aesthetic, fed into a transgressive, anti-authoritarian mode of critique. This is rendered through his unpacking of the figure of the film auteur, one that has historically enabled powerful individuals, operating under the pretence of artistic innovation, to exercise unquestioned control.

The most profound and insightful parts of Symbiopsychotaxiplasm, in terms of how they encapsulate the film’s politics, are accidental and unplanned. Most memorably, Victor, a random passer-by whose rambling charisma is strangely endearing, quickly discloses that he is an unhoused artist. The crew, despite having shot for an entire week in the same park he claims to have been living in, respond in disbelief. “You’re full of shit,” he says. “You must have known … There’s an enormous amount of human beings here.” This scene, like others in the film, calls into question the political and aesthetic myopia of filmmaking, reminding us of the marginalised and excluded spectres that linger – both on and off screen.